In a PsychologyToday article entitled “The Perfect Amount of Stress” the author, Thea Singer, contemplates “when do we have too little stress and when do we have too much stress?” A good question, but likely an over-simplified one.

A better question might be: “When have we been overly programmed by stress and when do the costs of that adaptation outweigh the benefits?”

“Our goal isn’t a life without stress,” Stanford University neurobiologist Robert M. Sapolsky says. “The idea is to have the right amount of stress.” That means stressors that are short-lived and manageable.

While it is often true that the goal is to have short-lived stresses that are manageable.It is also true that a short-lived stress or an acute stresses can be just as, if not more, damaging. For example, a short stress can adapt a system inappropriately. Either making that system hyper-reactive or using resources like energy and nutrients ineffectively. A short term stress early in life can also make other stressors occurring later in life more stressful than we’d typically expect.

A stress is ultimately something that elicits activation of the body and brain to tell us that something in our environment needs our attention. However, stress is not just immediate dangers like tigers, bears and sharks. Stress is also the plain and mundane. Stress keeps us alert, awake, active, adapting and reacting properly to all sorts of rewards and threats.

Stresses go in. Stresses go out.

Cortisol the Culprit

In linear science where one finds a single cause and a single cure, stress is represented by cortisol levels.

A linear approach looks at cause and effect in a straight line; a single cause, stress, creates a single reaction, cortisol. So the traditional way of seeing stress has always been an increase in cortisol. Cortisol is “Enemy #1“says most traditional approaches to mainstream medicine. However, we are just beginning to realize that this relationship is much more complex. Cortisol sort of pings into a major stress axis of the brain called the HPA axis which pings with another axis called the HPG axis and then goes off in many different directions affecting many different neural, chemical and genetic pathways. It does this attempting to maintain balance, or what is called in scientific terms, homeostasis. And this depends on many factors within each person. This is why stress is personal and we can say “stress is different for everyone”. However, stress also follows very distinct patterns, rules and trade-offs. So when we talk about stress we are talking about a type of science with complex rules to follow to understand how and why those differences occur.

Cortisol is a very simple way to see the first action that stress takes on our body. Cortisol is an extremely important part of our everyday experience. We need cortisol, or stress. Some of us wake up because of rising cortisol levels, some drink coffee to raise their cortisol levels. The cortisol alerts our brains to ‘wake up’ to the world.

Bruce McEwen, stress expert states in the article:

Yet there is no uniform right amount of stress. Each of us has a different stress threshold—that is, the degree of stress needed to benefit or harm us—depending on our history and even our genetic makeup. For sure, there are events that are universally rated high stress: you lose your job or a loved one, a tropical storm floods your basement. But what matters most regarding health and even longevity is not the event itself but how you respond to it. And how you respond—emotionally and physiologically—depends on how you perceive it.

Emotions the Cause

Again in a linear framework where we look for a single cause, we think of the cause of stress as an emotional event. This is why for so long stress was thought of as something purely in the mind. Something that could only create emotional or social consequences. Now we know differently, but we are still looking at stress in a straight line. The emotional stress creating some basic physiologically problems. That was a huge leap for many scientists to make. The crossing over of the mind to the body. But now we are realizing that that huge leap was really just a small chasm. The real world of seeing the mind and body connected takes us to the core of how we view the world. Epigenetics is just one aspect of this new science of how the environment touches upon our genes and how our genes create our reality of both our minds and our bodies. But when it comes to stress, stress is the core of that communication channel. The definition of stress as a cause, once emotional, has become the backbone of every piece of communication that comes from our environment that will determine how resilient we are.

This includes genes, nutrition (calories, fats, minerals, vitamins, sugars), as well as, our microbiome, hormone and hormone disruptors, our physical fitness, and of course or social, family and community support.

But in the mainstream there is still this fight it seems to make how we respond to stress purely a conscious choice; attitude, perception, grit.

While we certainly have a lot of power in how and when we perceive stress,this is just as much unconscious as it is conscious choice. How we perceive it may depend on our physiological internal state. Choice and attitude is a sliver in the stress perception pie, but it is only one slice and a slice that is deeply ingrained to other aspects of our physiology. As anyone on very little sleep can attest, their “attitude” becomes highly susceptible to their sensory environmental or social triggers. When in a more rested states would not bother them at all. If the “fight or flight” hits you are going to want to fight or flight, your options of choice have become limited. When your brain gets hit by adrenaline and cortisol, it gets flooded with these chemicals that can create adverse over-excitation. To calm that excitation, you need an outlet, control, calm, feelings of control. Without some kind of reaction to depress this activity, the brain chemistry in these overwhelmed states could create actual damage to the brain.

Knowledge of social support such as having friends, family community, cognitive reframing or a change in self-talk, meditation, relaxation or being in an enriched environments of activity and purpose are all part countering social stress with social resources.

For a stress be manageable. We need to rely on our ability to recover. Our ability to recover depends on our social resources, but also such things as our mineral supplies, our fatty acid balances, our symbiotic bacteria, our hormone messengers, and what may be draining our energy . It also depends on our ability to oscillate. If a stressor impairs our ability to go into proper and timely “healing responses” then this can begin to degrade the system. Stress becomes more stressful. Even if we have “constant stress”, if we have the proper resources to make that stress useful and are able to go into rhythms of recovery and healing phases, then constantly stressing or challenging our systems can be good for us.

Calming, adaptation, and re-adapting the brain.

The Stressed Out Brain (Inflammation throughout the )

A reaction is mandatory or the brain becomes damaged. One such example of something that “soothes” these chemical, is high sugar-fat foods. High caloric energy after a dreadful event can calm the chemicals. This protects the neurons from damage, it tells the brain its safe to calm down because it has extra energy to get the job done.

However, as we also know, high sugar/fat diets are bad for us. The are bad for us because while the calm the brain, they stress the body even more. Too much sugar and fat together create the same impact as early life stress. sugar-fat diets can create major problems in development or stress reactivity programming later on in life. This is because excessive energy in the form low quality and early life excessive and chronic sugar and/or fat exposures can have the same impact as early life stress, programming the brain/body for later life disorders and illnesses.

Our thought process or attitude toward challenges is part of that perception, however so is our biology, immune, neurobiological, nutritional status and our current load of other stresses. As well as our current level of thresholds and our biological coping patterns of the past which is reflected in the science of adaptation and epigenetics.

So in much this way stress is not about how long or short it is, but what kind of recovery, adaptations, trade-offs and resources we have.

The story worsens if the threat continues—that is, if the stress becomes chronic. Then you experience what neuroendocrinologist Bruce McEwen of The Rockefeller University, in New York City, calls toxic stress—you’re overwhelmed and feel out of control. “Things are coming at you left and right,” he says. “You can’t keep up with them. There is the danger of developing a sort of ‘learned helplessness’ “—that is, not even trying to cope anymore because you feel there is no point. “The more threatened you feel, the less capable you feel,” says McEwen, “and the worse your physiology is going to be as a result.”

Chronic and Toxic Stress

This new perception of stress isn’t about long or short, chronic or acute, it’s about adaptation. While we may say “everyone is different” in how they handle stress, we still want to think in linear terms of resilient or not resilient. That’s the confines of a linear model.

stress isn’t about long or short, chronic or acute, it’s about adaptation. While we may say “everyone is different” in how they handle stress, we still want to think in linear terms of resilient or not resilient. That’s the confines of a linear model.

When we take it to a nonlinear model we need “initial conditions” to create an algorithm of patterns, like a PLINKO Board. We do this so we can make educated guesses of who will be on which side of the spectrum. We need to incorporate human diversity into these equations. In order to do that we need starting points. And what we know about human behavior and reactions to stress is that we have personalities that reflect structure and function of neurochemicals that also respond in particular ways to stress.

Why Personalities Could Be The Key to a New Science of Stress. Genes

We like to oversimplify such matters as we all need to be the “best” at handling stress. But how we handle stress is an individual thing, a personality signature you might say. If one has say a personality that seeks novelty, or have more dopamine in the brain, then one’s in-born “chemical balance” is different than say one that is more stoic. You can’t, and it would be detrimental to try to make a novelty-seeker more stoic simply because you think that will make them more stress-resilient.

A stoic may be more naturally stress-resilient, but that may be in just one particular way or under a certain set of circumstances. For example having a good social support network may give their brains more of a chemical boost. Whereas it may not do the same for a novelty-seeker. That person may get more of a chemical boost from alone time or hiking and exploring. So it is more than just an “attitude” to see things as a challenge. It’s about  specifically find what works for you. Much like the popular “Love Languages“. Where how one person feels appreciated and love may be very different than another. So your husband may feel he’s showing you love by mowing the lawn, but you feel love by touch and affection. He may love you, but you won’t get that chemical hit of love (oxytocin) that can make you more stress resilient unless he is also holding your hand at the movies.

specifically find what works for you. Much like the popular “Love Languages“. Where how one person feels appreciated and love may be very different than another. So your husband may feel he’s showing you love by mowing the lawn, but you feel love by touch and affection. He may love you, but you won’t get that chemical hit of love (oxytocin) that can make you more stress resilient unless he is also holding your hand at the movies.

Our Resources

The classic or colloquial definition of what we mean by the word “stress” is when we are overwhelmed to the point of being irritable, worn-out, anxiety ridden or exhausted. We think of stress as our social world creating mostly emotional consequences but also the accepted physical consequences such as high blood pressure, irritable bowel, ulcers or belly fat. When we go to the doctor for bothersome symptoms the doctor can’t explain, the typical scapegoat is that it’s “just stress”. Something there is no real physical reason for, but something in your mind is either making up or manifesting symptoms that is out of your doctors control and is somehow your own responsibility for not being “resilient enough”.

Someone who’s generally anxious is likely to see a stressor as a threat, while someone who’s resilient will see that same stressor as a challenge. In the anxious person, the prefrontal cortex—the seat of executive function—may be less well-developed and thus have less control over the amygdala and its access to fear memories.Strong or Resilient is a False Dichotomy

Stressed states of adaptation can impart both positive and negative affects. A mouse that can no longer learn a new maze is also more protective and processing peripheral information at greater capacities. They become impaired in one way, to become more highly talented in another.

“Someone who’s generally anxious”, you could just as easily say someone who is more highly attuned to their environment, which is also a benefit. Mainstream medicine typically wants to see all problems as deficits or dysfunction. However, a new way to look at problems of stress, is as problems of stress balances and trade-offs.

This creates an assumption of a linear dynamic or dichotomy that there are “anxious” people and “resilient” people, when this dynamic in my experience crosses over and depends on the situation and coping strategy. “Resilient” people would typically fall in the stoic temperament, but their resilience may actually, when under stress, be their downfall. They are more resilient because stress downregulates so they feel less pain. Whereas an “anxious” upregulates in an attempt to protect. They are both equally compromised in their own unique ways.

For example, let’s say a stress adapts a system to become hyper-vigilant when that vigilance is not needed. We could think of this in terms of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Where an acute or overly intense and long state of stress has adapted the system in such a way as to bring on a myriad of psychological, physiological, digestive and immune conditions. The body/mind has become more over-reactive than necessary in its current environment (although it may have been appropriate for its most recent past environment). and is using resources ineffectively (for its current environment and opportunities) and it is staying inefficiently in “protect” mode instead of healing and growth modes. It needs either time, extra resources, or a “retraining” or re-adaption to a more lower level of excited state.

For example, let’s say a stress adapts a system to become hyper-vigilant when that vigilance is not needed. We could think of this in terms of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Where an acute or overly intense and long state of stress has adapted the system in such a way as to bring on a myriad of psychological, physiological, digestive and immune conditions. The body/mind has become more over-reactive than necessary in its current environment (although it may have been appropriate for its most recent past environment). and is using resources ineffectively (for its current environment and opportunities) and it is staying inefficiently in “protect” mode instead of healing and growth modes. It needs either time, extra resources, or a “retraining” or re-adaption to a more lower level of excited state.

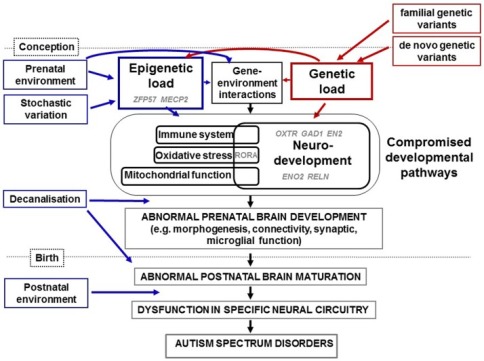

Autism

But to this, there may impart certain advantages because as Justin Storbeck shows us from his studies and as Jeff Hawkins suggests in his book “On Intelligence” the emotional, affect is directly connected with or goes hand-in-hand with cognitive processing. So our emotional states of “protection” whether  hypervigilant or energy-saving, may impart other trade-offs that are “positive”. An example of this is in Autism “splinter skills“. Splinter skills are more commonly known in its extreme f0rm as beig a savants. “Gifts” of unbalanced systems, or overly-sensitive systems. Systems that may be alternately adapted to the “real” world. Amplified information processing features that are bound to affective (emotional) systems. Autism in this manner could be a heightened sensitivity and increased information along with high anxiety and awareness. With excessive information processing also come excessive resource draining like brain glucose and energy trade-offs (for other developmental projections). Greater information processing, capacity, strength and memory, can be associated with skill-sets in math, science, art and music. Does autism create these gifts or did we already have them and early life stress programming amplify them, with the subsequent corresponding trade-offs. Trade-offs like anxiety, sensory overwhelm, energy exhaustion, food disorders, digestive and immune issues?

hypervigilant or energy-saving, may impart other trade-offs that are “positive”. An example of this is in Autism “splinter skills“. Splinter skills are more commonly known in its extreme f0rm as beig a savants. “Gifts” of unbalanced systems, or overly-sensitive systems. Systems that may be alternately adapted to the “real” world. Amplified information processing features that are bound to affective (emotional) systems. Autism in this manner could be a heightened sensitivity and increased information along with high anxiety and awareness. With excessive information processing also come excessive resource draining like brain glucose and energy trade-offs (for other developmental projections). Greater information processing, capacity, strength and memory, can be associated with skill-sets in math, science, art and music. Does autism create these gifts or did we already have them and early life stress programming amplify them, with the subsequent corresponding trade-offs. Trade-offs like anxiety, sensory overwhelm, energy exhaustion, food disorders, digestive and immune issues?

We all have these associated affect-processing dynamics to some extent. In the condition of autism this could amplified, both skills and emotions. When we become hyper-vigilant emotionally the brain’s cognitive and information processing, awareness and organization also become hyper-vigilant. But in Autism it acted on systems, or personality styles that may have already been particular programmable by stress.

Autism isn’t an epidemic of a disease or random mutation, it’s a revolution of how we can visualize and conceptualize a new science of stress adaptation.

Autism isn’t an epidemic, its an opportunity to discover the human potential, our environmental downfalls and our future direction.

It is negative because “stressed” is like running on massive amounts of fuel you weren’t prepared to have, so the body has to make compensations to other organs, like digestion, that required energy. In this way it becomes degrading to the system. It is not stress acting directly, but indirectly on these systems. Stress doesn’t cause damage it causes change and adaptation, the damage comes when the adaptation is inaccurate, inadequate, false or excessive to the situation.

“People who are prone to anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, or depression have imbalances in those circuits and their underlying chemistry,” says McEwen. “And that makes them react to a situation in a more anxious way than another person. So, the idea of how much stress is too much is as much an internal or individual problem as anything else.”

People “who are prone” may not be a label of disorder but rather a function of their tendencies of personality and information processing that is more likely to become unbalanced and present as a particular disorder. A function of sensitivity and flexibility to one’s environment may impart certain trade-offs in function that also create susceptibilities.

It’s not only a slippery slope of cost-benefit reactions (and brings to question “when” is it exactly a disorder), but it also means that there can be “many roads to Rome”. That even when you have the susceptibility someone else without the susceptibility may get to the same place but through different routes. . The idea of stress as an individual thing is absolutely true because it is the system (systems thinking) that is always at the core of interacting with one’s environment. It’s not the “stress” that is the cause, it is the “system” that is its own cause of threshold, coping, and trade-offs.

Stressed states can lower what is called latent inhibition, the amount of information that is billowing into your brain. It’s like having your brain always half-full of information, so constantly burning energy, constantly on the threshold of stress overwhelm. The point of stress-responses and need for resources always heightened. How one experiences, copes and hits a point of stress is an individual and internal mechanism. The concept of stress being alleviated by “positive reframing” is essential, but also a failing perspective because it doesn’t truly incorporate individuality, the multiple avenues reducing stress resiliency, nor the process of epigenetics, or the adaptation aspects that occur. Stress is about a lot more than whether it is “good” or “bad”, stress is about information and appropriately, adequately, effectively without too much sacrifice, responding to the environment.

Stress is essentially too much work and not enough resources to do it. It’s the way in which we can communicate, react and adapt to our environment.

Much of how one responds or adapts to stress is about resources. Resources compound and impact one another. If one does not have adequate nutritional resources you can physiologically respond more emotionally to threats. Healthy challenges can become unhealthy threats. Just as it is true that if one has a lot of social support you don’t feel as threatened by smaller incidents or can create or speed recovery from seemingly unrelated phenomenon, like heavy metal poisoning or cocaine withdrawal. Something like exercise that can at first be a threat, can become a resource. Feeding the brain necessary chemicals that help abate stress and give the system reassurance and messages that it is strong, capable and resilient.

Social stress has a special place among all the other factors that impact our stress levels and resilience. We don’t survive without others, we don’t survive without support and we don’t survive without love, attachment and nourishment. Even though many of these stress/pain pathways run the same circuits are assessed by the same “motherboards” within our physiology. Social stress like isolation and threats (like virus like viruses) can many times create the most impact. A double or triple hit can be what creates more programming issues (we can’t look at stress in isolation). One stress, compounded by others stressors, create greater impact. So the interaction of a multitude of stressors can lower our threshold for perceived threats and increase our need for social support. We just have to start viewing these things as interactive and that social stress does not act alone. And just because social resources or support can be a solutions doesn’t necessarily mean it was the cause.

Adaptation, Programming. Re-adaptation and Re-Programming.

Kids need environments which are low on stress, and high on belonging, which can activate, or accelerate, motivation. If this sounds obvious, consider why it is so critical: When kids are exposed to moderate, or high levels of stress, the biology of their brains changes. They are less able to perform complex intellectual tasks and regulate their emotions. Working memory is impaired. As adults, they are at higher risk of cancer, heart disease and emphysema. (From Quartz)

The problem with taking a linear approach to stress, is that you now have a choice between high or low, short or long stress. Stress is consider a single source and typically stress is thought of as social. It comes from the previous misconception that the mind and body were separate. That stress may create some physical symptoms, but it was still just from your brain and your attitude or mental issues. However, this doesn’t even begin to encapsulate the complicated nature of the term “stress”. Stress is a fundamental way in which we balance and thrive in our environments. We don’t want low stress, we want enough resources and the right balance of stress. The recent book “Grit” gives us this same type of misconception that what we need is low stress. We as a society have just had this complete misconception of what stress really means. Stress is information and challenges. With that definition would we ever say we want “low” stress? Or is it about having this incredibly strong social and nutritional foundation to take on stress so that it oscillates properly and we don’t have constant unrelenting stress that can’t be countered by resources stress that is now adapting these brains improperly?

Linear causal stress (cortisol) creates the known creation of things like ulcers, high blood pressure and the like. These are sort of clear and direct. Whereas the nonlinear causal impacts of stress are more insidious and have to do with early life programming, improper responses to the environment, later life development of disease. These are the diseases and disorders of great mystery, from autism to Alzheimer’s, cancer to heart disease.

Yet, regardless of your upbringing or personality, there is good news: Science has shown that we can all alter our perceptions. We can, with training, transform a threat into a challenge. We can even stress proof our brain, raising our overall stress threshold. And when stressors subside, most of the damage—retracting dendrites, for example, or an overgrown amygdala—can be reversed. We can improve our overall health and add years to our lives (From Quartz)

Is it really a matter of simple dualism? Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in body and mental health. anssen D, Kozicz T. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00028. Epub 2013 Mar 12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3594922/

Nutrition, adult hippocampal neurogenesis and mental health. Br Med Bull. 2012 Sep;103(1):89-114. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds021. Epub 2012 Jul 24.Zainuddin MS, Thuret S. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22833570

Impact of diet on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Doris Stangl and Sandrine Thuret. Genes Nutr. 2009 December; 4(4): 271–282. doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0134-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2775886/

What’s New? Exuberance for Novelty Has Benefits. JOHN TIERNEY Published: February 13, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/14/science/novelty-seeking-neophilia-can-be-a-predictor-of-well-being.html

Dietary levels of pure flavonoids improve spatial memory performance and increase hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Rendeiro C, Vauzour D, Rattray M, Waffo-Téguo P, Mérillon JM, Butler LT, Williams CM, Spencer JP. PLoS One. 2013 May 28;8(5):e63535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063535.

Acute stress and chronic stress change brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tyrosine kinase-coupled receptor (TrkB) expression in both young and aged rat hippocampus. Shi SS, Shao SH, Yuan BP, Pan F, Li ZL.Yonsei Med J. 2010 Sep;51(5):661-71. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.5.661.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20635439

Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2009, April 8). How Men And Women Cope Differently With Stress Traced To Genetic Differences. ScienceDaily. Retrieved June 2, 2013, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/04/090405185031.htm

Gender differences in reward-related decision processing under stress. N. R. Lighthall, M. Sakaki, S. Vasunilashorn, L. Nga, S. Somayajula, E. Y. Chen, N. Samii, M. Mather.Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2011; DOI: 10.1093/scan/nsr026

By Sherry Baker, published on January 1, 2007 – last reviewed on June 9, 2016

https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/200701/the-sex-hormone-secrets

Improved Working Memory but No Effect on Striatal Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Type 2 after Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3463539/

Dietary Polyphenols as Modulators of Brain Functions: Biological Actions and Molecular Mechanisms Underpinning Their Beneficial Effects. David Vauzour. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012; 2012: 914273. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3372091/

Roles of melatonin in fetal programming in compromised pregnancies. Chen YC, Sheen JM, Tiao MM, Tain YL, Huang LT. Int J Mol Sci. 2013 Mar 6;14(3):5380-401. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035380. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23466884

Priyadarshini S, Aich P (2012) Effects of Psychological Stress on Innate Immunity and Metabolism in Humans: A Systematic Analysis. PLoS ONE 7(9): e43232. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043232 http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0043232

On the interdependence of cognition and emotion. Justin Storbeck and Gerald L. Clore. Cogn Emot. 2007; 21(6): 1212–1237. doi: 10.1080/02699930701438020

Psychosocial stress induces working memory impairments in an n-back paradigm. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18359168

Stress Breaks Loops That Hold Short-Term Memory Together. http://www.newswise.com/articles/stress-breaks-loops-that-hold-short-term-memory-together

The beautiful otherness of the autistic mind. Francesca Happé, Uta Frith. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 May 27; 364(1522): 1345–1350doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2677594/

Performance costs when emotion tunes inappropriate cognitive abilities: implications for mental resources and behavior. Storbeck J. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012 Aug;141(3):411-6. doi: 10.1037/a0026322. Epub 2011 Nov 14.

Hippocampal volume and mood disorders after traumatic brain injury. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17123480

Novel and Functional Norepinephrine Transporter Protein Variants Identified in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2801604/

Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation restores mechanisms that maintain brain homeostasis in traumatic brain injury. Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F.J Neurotrauma. 2007 Oct;24(10):1587-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17970622

Dietary curcumin supplementation counteracts reduction in levels of molecules involved in energy homeostasis after brain trauma. Sharma S, Zhuang Y, Ying Z, Wu A, Gomez-Pinilla F. Neuroscience. 2009 Jul 21;161(4):1037-44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.042. Epub 2009 Apr 21.

There Is No News Like Bad News: Women Are More Remembering and Stress Reactive after Reading Real Negative News than Men. Marie-France Marin, Julie-Katia Morin-Major, Tania E. Schramek, Annick Beaupré, Andrea Perna, Robert-Paul Juster, and Sonia J. Lupien,PLoS One. 2012; 7(10): e47189. Published online 2012 October 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047189. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3468453/

Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. Brain Res Rev. 2008 Mar;57(2):571-85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.004. Epub 2007 Nov 28. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18164765

DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus and amygdala of anxiety-prone versus risk-taking rats. Simmons RK, Howard JL, Simpson DN, Akil H, Clinton SM. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34(1):58-67. doi: 10.1159/000336641. Epub 2012 May 8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22572572

Social-evaluative threat and proinflammatory cytokine regulation: an experimental laboratory investigation. Dickerson SS, Gable SL, Irwin MR, Aziz N, Kemeny ME. Psychol Sci. 2009 Oct;20(10):1237-44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02437.x. Epub 2009 Sep 14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19754527

Targeted Rejection Triggers Differential Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Gene Expression in Adolescents as a Function of Social Status. M. L. M. Murphy, G. M. Slavich, N. Rohleder, G. E. Miller. Clinical Psychological Science January 2013 vol. 1 no. 1 30-40. http://cpx.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/09/07/2167702612455743.full

Association for Psychological Science (2010, April 28). Merely seeing disease symptoms may promote aggressive immune response. ScienceDaily. Retrieved June 8, 2013, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/04/100427111248.htm